When an investigation meeting derails: the cellphone incident and a 90-day trial period appeal

This is an anonymised write-up based on an ERA determination from 2025. The legal issue is real. The human moment was painfully real too.

What the case was about

The case involved a personal grievance alleging unjustified dismissal, where the employer relied on a 90-day trial period clause to say the employee could not bring an unjustified dismissal grievance. The employee also raised issues about hours and pay.

The Authority ultimately found the unjustified dismissal claim did not succeed because the dismissal was treated as occurring under a valid trial period, and the employee was therefore barred from bringing an unjustified dismissal personal grievance in respect of that termination. The Authority did, however, make findings and orders around minimum hours and holiday pay calculations on outstanding amounts.

The legal argument we say was not dealt with

A central issue in many trial period cases is strict compliance. Trial provisions remove the usual right to bring a personal grievance for unjustified dismissal, so the courts have repeatedly emphasised that the statutory requirements must be complied with strictly.

In this case, we argued that the employer could not rely on the trial provision because the termination notice requirements in s 67B(1) were not satisfied in substance at the time. In particular:

- no notice period pay was processed at the time of dismissal, and

- there was no evidence of final pay being processed through payroll/IRD reporting at the time, and

- the employer later attempted to backfill payment roughly a year later, after the case had been underway.

The point is not about turning employment law into a game of "gotcha". It is about whether the employer can rely on a statutory bar that removes a longstanding employee right, when the statutory preconditions were not met at the relevant time.

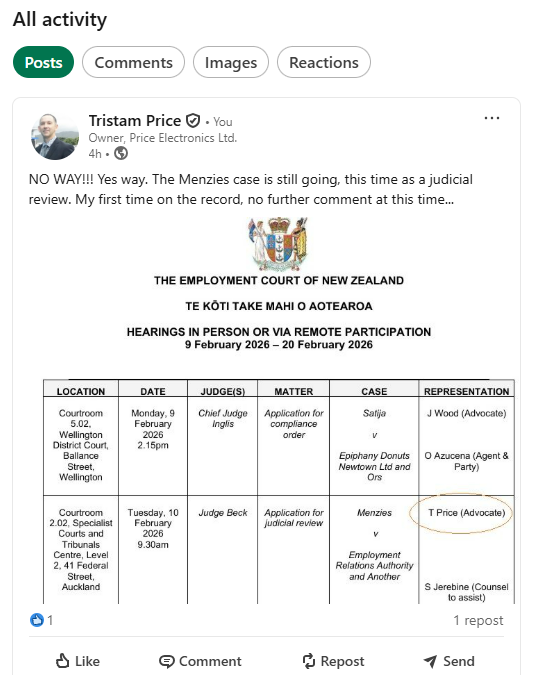

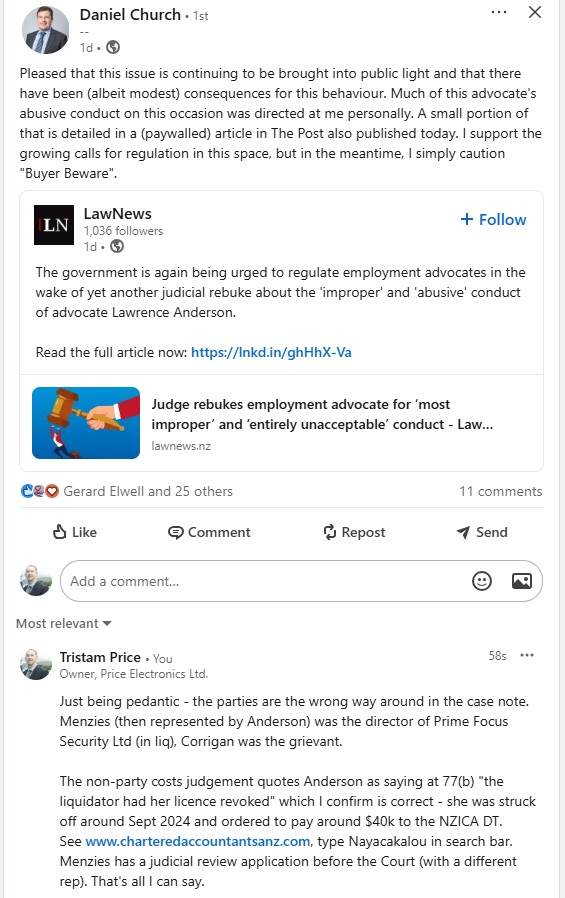

The problem for us is that the determination did not grapple with that argument in a way that lets the parties (and the Employment Court) understand why it was accepted or rejected. That is one of the grounds for challenging the determination in the Employment Court.

The investigation meeting incident

Now for the part that every advocate dreads.

During the investigation meeting, after my client had given evidence and had been questioned by the Authority Member, my client started using his cellphone. A moment later, the phone played audio loudly enough for people in the room to hear: "how to use your device for intense masturbation!".

It was not planned, not strategic, and not helpful. It was an embarrassing disruption in a formal process where credibility and focus matter.

I cannot control a client's hands once they are sitting in a hearing room. I can prepare them, warn them, and intervene when something happens, but I cannot run the person like a remote-controlled device.

Could that have influenced the result?

A Member is obliged to decide the case on evidence and law. The test is what a fair and reasonable employer could have done in all the circumstances, assessed objectively. That is the legal standard.

But advocacy is conducted in the real world. People are human. A sudden, loud, explicit phone video in an investigation meeting is the kind of event that can shift the room in an instant. Even if the Member tries to put it aside, it can affect how seriously the evidence is received, how credibility is subconsciously assessed, and how much patience exists for the finer points of statutory argument.

If you are wondering whether that should matter, I agree: it should not. It is not evidence about the employment relationship. But it happened, and pretending otherwise would be naive.

What I would do differently next time

- Pre-hearing briefing: I now explicitly instruct clients: phones off, in airplane mode, out of reach.

- Seating and control: where possible, keep devices in a bag or with the advocate during evidence.

- Fast intervention: if anything starts playing, interrupt immediately and request a short adjournment.

- Refocus on the legal issue: bring the discussion back to the statutory requirements and the Authority's duty to deal with the arguments raised.

Practical takeaway

If your case turns on a technical legal gateway issue (like the validity of a 90-day trial period bar), you need: (1) clean evidence on the facts, (2) clear submissions on the statute, and (3) a hearing environment that does not sabotage credibility. That last part is not always within your control, but you can reduce the risk.

If you want a quick review of your situation (or you are not sure whether a trial period is valid), you can start here: Employee Unfair Dismissal Case Form.

Note: This article is general information, not legal advice for your specific situation. If you need advice, get tailored help.